Can your girlfriend give the cops permission to search your bag?

ALSO: Can 911 operators get workers’ comp benefits for PTSD? And are online ministers real ministers?

I love this case. This is bread-and-butter Constitutional Law, exactly the sort of case they put in textbooks to demonstrate how the Fourth Amendment’s protection from “unreasonable searches and seizures” plays out in real life. It’s the sort of case that makes me really miss law school.

I also love this case because the outcome turns on whether a black bag is a woman’s purse or, in fact, a “man bag.” (Yes, this is the language used by the court.)

So, because I don’t think people should have to spend almost $50,000 a year on a law degree just to know the basic rules of our society:

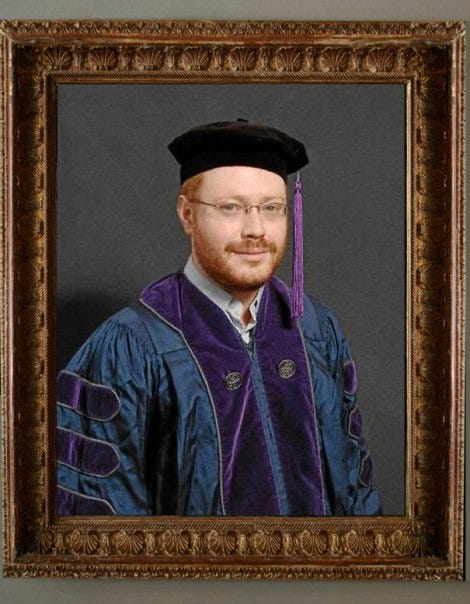

Welcome to the Unprecedented School of Law!

I’m Professor Schwartz. Since I once again failed to get the Defense Against the Dark Arts job, I’m teaching Constitutional Law — again. Let’s look at the facts of U.S. v. Williams, hot off the judicial presses from the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals (whose decisions affect Arkansas, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, and the Dakotas).

Mosley Jumon Williams had a warrant out for his arrest for armed kidnapping, and the cops picked him up in April of 2019. The detective searched his car, but couldn’t find the gun he allegedly used in the kidnapping. So while Mr. Williams used the prison phone, the cops listened in, hoping he would slip up.

Sure enough, on a call with his girlfriend Wanda, Mosley was asked if he had left “the thing” at her place. Mosley said he did, and told her to put it “inside of the closet and forget about it.” The detective — clearly a master code-breaker — deduced that “the thing” might be the missing weapon.

So the next day, he and three officers knocked on Wanda’s door. She admitted that she had a gun, which she sometimes let Mosley use. She agreed to show them the location of the gun, and escorted them to the bedroom. There, hanging from the handle of the open bedroom door, was a partially unzipped bag clearly containing a gun.

Wanda then agreed to let them search the apartment. The detective opened the bag — which he described in the police report as a “man bag” — and found the handgun they were searching for, as well as 14 grams of methamphetamine and a letter addressed to the boyfriend at a different address. With this evidence, they charged Mr. Williams with additional gun- and drug-related offenses.

Mosley’s attorney asked the judge to throw out the evidence they got from the warrantless search of the bag, claiming the girlfriend didn’t have the authority to consent to the search.

Was that an “unreasonable search and seizure”?

OK, class, let’s talk about the Fourth Amendment. Open your Pocket Constitution to the Bill of Rights. It’s at the end.

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

In other words, before an officer can search a residence, he needs a warrant, which he gets by convincing a magistrate judge that it’s very likely they’ll find relevant evidence there.

Now, the Supreme Court has said that the police don’t need a warrant if they get consent. The question then becomes: Can you give the police permission to search through someone else’s property? Generally speaking, the answer is no — but if you do give permission, and the police genuinely believe that you had “authority” to give consent, then the search will be allowed.

This can get confusing, and it’s highly fact-specific. The Supreme Court has spent the past several decades trying to figure out what to do in these situations, and a couple of key cases will shed some light on it. Who’s ready for fun fact patterns? Because you’re about to read some fun fact patterns!

U.S. v. Matlock (1974): A suspected bank robber was arrested in the front yard of the home he had been living in. When officers approached the front door, a woman wearing a robe and holding a young child gave permission to search not just the house, but also the bedroom she shared with the suspect.1 The court said this is fine — anyone who has “common authority” over a home (a housemate, a spouse, etc.) can consent to a search. As Fourth Amendment scholar Orin Kerr has explained: “When you chose to live with someone and share space with them, the thinking goes, you generally assume the risk that she might consent to a search.”

So we know that someone you live with can consent to a search of your home. But what if it’s someone you don’t live with?

Illinois v. Rodriguez (1990): The police were called to the home of a woman whose daughter Gail had been severely beaten. When the cops arrived, she told them Eddie did it. He’s asleep in our apartment, she said. I’ll take you there. Gail went with the cops to Eddie’s place, where she pulled out the keys and unlocked the door. The cops walked in, found cocaine and drug paraphernalia all over the apartment, and woke Eddie up to arrest him for drug crimes.

Eddie’s lawyer moved to suppress all that evidence, since it was Eddie’s place, not Gail’s — she wasn’t on the lease, didn’t pay rent, and hadn’t actually stayed there in weeks. A solid argument, yes?

Not solid enough! The Supreme Court sided with the police, reasoning that cops are going to face a lot of situations when they have to make a judgment call as to whether someone has the power to say Yes, you can search this house. It’s not necessary that the police “always be correct, but that they always be reasonable,” the court wrote. This case stands for the principle that if the police reasonably believe someone has apparent authority to consent to a search, the search will be valid.2

About that Man Bag

Remember, the detective wrote in the police report that the bag containing the gun looked like a “man bag.” And the first two judges to examine this case found that fact so important that they used it as a reason to throw out the evidence.

Why is calling it a “man bag” so crucial? Because it implies that the detective had reason to believe the bag didn’t belong to Wanda. Remember, the police have to “reasonably believe” someone has authority to agree to a search. “Because the gun was located in a bag that appeared to belong to a man,” the magistrate judge wrote, “at a minimum, [the detective] should have attempted to clear up ownership of the ‘man bag’ before conducting a warrantless search.”

The government appealed, arguing that although the detective wrote down “man bag” in the police report, he had also described it during a hearing as just a generic bag, and he didn’t really know who owned it.

This is a photo of the actual bag in question, straight out of the government’s reply brief to the court. Does this look like a “man bag” to you?

As the government attorneys wrote, the bag can “best be described as a nondescript, unisex messenger bag or laptop bag ... And, in any event, the ‘gender’ of the bag is in no way dispositive of whether it belonged to [Wanda]; even if it were a ‘man bag,’ nothing would preclude her from owning it.”

And the Eighth Circuit ruled in favor of the government — the search was okay! “The district court clearly erred in finding the bag was a ‘man bag’” that couldn’t have also belonged to Wanda, the court wrote. A “person of reasonable caution” would be more than justified in thinking Wanda was able to consent to the search.

In conclusion: Yes. Your girlfriend can indeed give the cops permission to search the bag you left at her apartment — but only if she leads them to believe it might be her bag. (If Wanda had said, “Well, officer, my boyfriend’s bag is over there but I’m not allowed to go through it,” this case would have turned out very differently.)

Can 911 operators get workers’ comp benefits for PTSD?

TRIGGER WARNING: Violence... directed at babies.

The Schwartz Report is not the kind of publication that you can expect to see a lot of “trigger warnings” in. We feel it’s important to be able to move through the world without covering your eyes when confronting the painful realities of life.

But this case out of Iowa is just too much. If you are an expectant parent, a new parent, or really a parent at all, you might want to skip to the next case.

Okay, here we go.

For 16 years, Mandy Tripp had been answering tens of thousands of 911 calls, ranging from the mundane to the life-threatening. But none of those calls prepared her for what she heard on the line that autumn day in 2018.

“Help me, my baby is dead!” a woman screamed over and over. “Help me, my baby is dead! Help me, my baby is dead!” The screaming continued for over two minutes.

After getting the address, Ms. Tripp transferred the call to a medical dispatcher. But she could still hear the radio traffic: Emergency medics who arrived at the scene to find the baby stiff and unresponsive. (“Rigor was already set in,” she heard them say.) Police officers talking about a crime scene, about injuries to the child’s face. The baby looked like it had been beaten to death with a hammer.

And all the while, in the background, those screams. Ms. Tripp described them as “guttural, awful.” She couldn’t get the sounds out of her head. Over the coming days she was sullen, on the verge of tears. In the ensuing months, she found herself constantly crying, battling nightmares, and becoming socially withdrawn. She was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. She struggled with suicidal thoughts. High-pitched noises caused her to panic. She started wearing special earplugs when she left the house. Sometimes, when the noises were especially loud, she wore noise-cancelling headphones on top of those.

In Iowa, the law says that workers can get compensation “for any and all personal injuries sustained by an employee arising out of and in the course of the employment.” Ms. Tripp filed an application for workers’ compensation for PTSD.

Ms. Tripp was denied.

Why? Because of how the Iowa Supreme Court had interpreted that statute. PTSD definitely counts as an injury, but for a long time, the court had a higher bar for “mental injury” like PTSD: The employee has to show that the mental injury resulted from “workplace stress of greater magnitude than the day-to-day mental stresses experienced by other workers employed in the same or similar jobs.”

In other words, was a call from a grieving mother the sort of mental stressor that a 911 operator might expect as part of the job? The workers’ comp examiner said Ms. Tripp failed to prove that the call was unusual or unexpected. She appealed the ruling, but the district court agreed with the examiner. It’s just part of the job. Denied.

But the Iowa Supreme Court had been cultivating a different way of looking at mental injuries — those caused by a “manifest happening of a sudden traumatic nature from an unexpected cause or unusual strain.” What exactly does that mean? Until this month, the state’s high court had never elaborated. Now, the court took the opportunity to ponder the fairness of the word “unexpected” as it applies to emergency responders:

If the injury has to be caused by an “unexpected” strain, that puts emergency responders like Ms. Tripp at a disadvantage compared to workers overall. “They would bear a burden to prove hyper-unexpected causes and hyper-unusual strains — some extraordinary species of traumatic event, above and beyond the perilous events that they regularly confront — to qualify for benefits that those in less hazardous professions receive by meeting a far lower bar.”

That, the Iowa Supreme Court held, was unjust. They reversed the lower decisions, and approved Ms. Tripp’s workers’ comp benefits. Their decision, they said, brings mental injuries in line with the physical injuries already covered by workers’ compensation law for first responders — police officers, for instance, can get workers’ comp if they are physically injured in a high-speed car chase, even though police officers are often engaged in high-speed chases.

The case is an interesting example of our 50-state system at work, the various states all eventually coming to similar conclusions when confronted with the same social questions. Even though the language of workers’ compensation statutes differs by state, other courts have handled it the same way. In Arizona, an officer was able to get PTSD benefits after a shootout with a gunman during a welfare check — even though the gun-fight was foreseeable in the normal line of duty for a police officer. In Illinois, an officer got benefits after a standoff with someone he thought had a gun.

Generally, as long as the mental injury can be traced back to a specific incident — “help me, my baby is dead!” — rather than just generally getting worn down from stress, workers’ compensation covers first responders’ claims of PTSD.

Are online ministers real ministers?

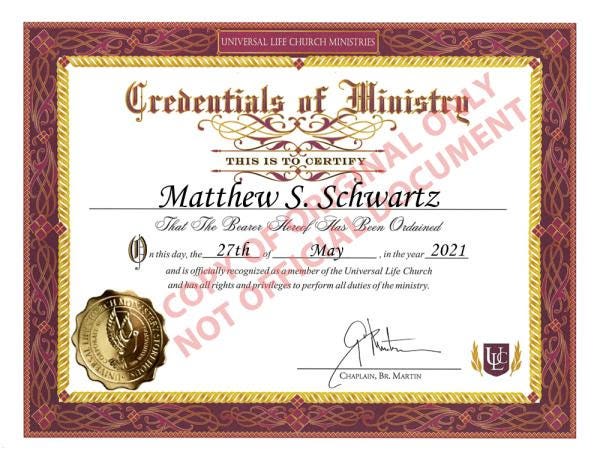

A little known fact: Matthew S. Schwartz, editor of The Schwartz Report, is an ordained minister. This is true! Look:

A little over a year into the pandemic, I was so utterly bored and directionless, I decided to fill in a questionnaire on the Universal Life Church website, and within a few minutes I had this official “not official” certificate in my e-mail inbox. #Ordained, the email said. Now I can marry my friends!

Except, not so fast. It turns out that while many states are cool, and will let just about anyone perform a wedding ceremony, other states are lame. These states include my home state of Virginia — which considers online ministries suspect — as well as Tennessee, where the attorney general’s office has looked down upon online ministries for decades, and whose state legislature in 2019 officially prohibited “persons receiving online ordinations from solemnizing the right of matrimony.”

The Universal Life Church Ministries (my sect!) quickly sued the state, claiming the law violates the First Amendment by discriminating against certain religions (the online kind), and the Fourteenth Amendment by denying them due process.

(A few things to know about the Universal Life Church Ministries: We apparently have a few main beliefs: 1) All individuals are equal — we are all “children of the same universe.” 2) Faith is personal — “as unique as the individuals who practice it” — and we can practice it however we like. 3) Always “do that which is right” — i.e. support projects that create positive change, and try to help your community. Seems like as good a religion as any.)

The judge in 2019 said the lawsuit raised “serious constitutional issues,” and issued an injunction that allowed online ministers to keep performing legal marriages while the suit was pending.

And now, finally, three years after the suit was first filed, after much legal wrangling over whether the Universal Life Church even has standing to sue, a federal circuit court has decided... that the case can go forward, in some limited form.

It is an unsatisfying opinion. It doesn’t get into the merits of the issue at all, doesn’t discuss the First Amendment, doesn’t wax rhetorical about the interplay between government and religion, doesn’t have a single “a priest, a rabbi, and an online minister walk into a bar” joke.

But the opinion does mean that the case will continue. And so the American legal system will, at some point, have to wrestle with the shifting definition of religion. (I think the Universal Life Church will ultimately prevail; the real question, as I see it, is what happens when I try to get a minister from the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster to officiate my wedding?)3

And that’s the Schwartz Report! We’ll be back in a day or two. If you’ve enjoyed this newsletter, please leave a comment, forward it to a friend, click that little heart button on the website, and share it far and wide. And if you really want to support my work, please consider becoming a paying subscriber. You’ll be supporting all the work we do here at Unprecedented, and you’ll also get access to occasional subscriber-only bonus segments.

Thank you for your support!

Sincerely,

Matthew S. Schwartz

Editor of Unprecedented

The woman and bank robber liked to tell people they were married, even though they actually weren’t. This isn’t all that relevant here; I only bring it up so I can mention that living together without being married “under circumstances that imply sexual intercourse” was a crime in Wisconsin in the early 70s.

One more case, just for fun, which shows the limits of who can give consent to search a house:

Georgia v. Randolph (2006): A married couple was fighting at their home, in front of the police. The wife, trying to get her husband arrested, told police that there was evidence of drugs inside the house. The officer asked the husband if he could search the house, and the husband said hell no. So the officer turned to the wife, who essentially said Yes, follow me, I will show you where the drugs are!, and proceeded to get her husband in a whole lot of trouble. In a 5-3 decision, the court explained, basically, that if two people live in a home and one invites you in for dinner while another tells you to get lost, common sense and social norms would dictate you do not go pull up a seat at the dinner table. Even if you live with someone, they can’t give permission to search the place over your own objection.

This is a real church. It started as a bit of joke, but it has been legally recognized in a few U.S. states. Let me know in the comments if you’re interested in a deep dive into alternative religions. It’s a fascinating subject!

The moral is, Don't use prison phones.

even your sister can get you locked up for years. i found out the hard way .