DEEP DIVE: “I want to shoot him in the face” (and keep my guns)

Are red flag laws the answer to our nation’s gun problem? Or are they wildly unconstitutional?

This week a bipartisan group of senators announced that, after decades of inaction, they have reached a tentative agreement to try to reduce the gun violence plaguing our country. The plan relies heavily on providing federal incentives for states to pass so-called “red flag” laws, which allow the government to temporarily confiscate guns from people who show signs of mental instability. (In other words, people who might commit a violent crime, even if they haven’t yet done anything illegal.)

It’s not surprising red flag laws are part of the expected legislation. Amid all the paralysis in Washington — amid all the vitriol and mistrust — red flag laws have long shown the most potential for bipartisan agreement. The one thing most liberals and conservatives agree on — to an unbelievable, basically unheard of extent — is that mentally unbalanced people shouldn’t have guns. (According to a 2021 Pew Research Center poll, 85% of Republicans and 90% of Democrats favor preventing the mentally ill from purchasing guns.)

There are still plenty of hurdles to pass before the federal government blesses1 red flag laws. Although moderate Republicans are on board, the more right-wing folks have a lot of objections, which implicate multiple amendments to the U.S. Constitution, not the least of which is the First Amendment’s freedom of speech. We’ll get to all that. But first, let’s look at one example of red flag laws in action to show how they might stop gun violence before it begins.

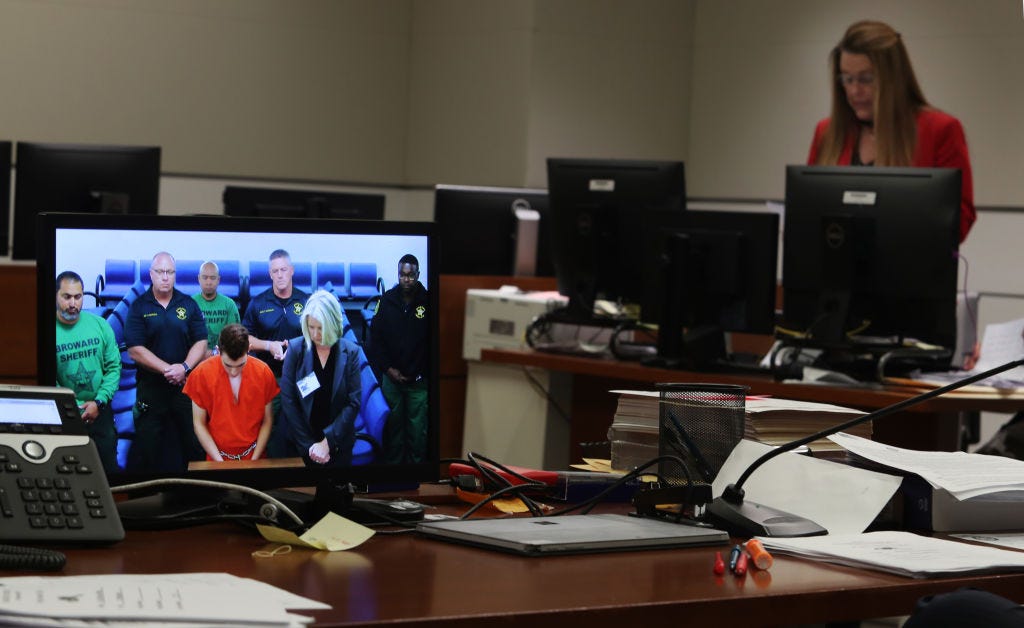

Preventing the Next Nikolas Cruz

In the years before Nikolas Cruz murdered 17 people at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida, the 19-year-old had had dozens of run-ins with the police. From the time he was a boy, his mother and others would call 911, warning about his collection of knives and guns, his violent temper, his anger issues. There were so many signs that something was coming, some of them explicit — like when he wrote in a YouTube comment section, “Im [sic] going to be a professional school shooter.”

None of the warnings did a thing to prevent the 2018 school shooting in Parkland, one of the worst massacres in U.S. history. The Republican-controlled Florida legislature was determined not to overlook such blatant red flags again. In the wake of the shooting, the state passed a law authorizing RPOs, which allowed police to temporarily confiscate guns from the mentally imbalanced.

One of the first Floridians to become the target of that law — known colloquially as a “red flag law” — was Chris Velasquez, a student at the University of Central Florida. Chris had praised the Parkland and Las Vegas shooters in Reddit posts. He called them “heroes,” and said of other posters, “You guys are too weak to be a school shooter” — the implication being that he, himself, was not too weak. Several Redditors contacted the police, and Velasquez soon found himself being interrogated by a police officer.

What follows is a master class in how to earn the trust of a suspect, how to get them to open up to you, and how to encourage them to reveal secrets they might not even be aware of themselves.

🏛 Special offer for new subscribers: Get a 30-day free trial to Unprecedented! 🏛

In the interrogation room

“Do you have any idea — and think about it, I think you do,” said Officer Jeffrey Panter of the UCF Police Department. “Do you have any idea why the police would be talking to you?”2

Chris said he thought it might have something to do with Reddit. Maybe something to do with a post he made a few weeks back that got him suspended from the site. “I have nothing to hide,” he told the officer. “If I need to clear the air, I’ll just clear the air right here.”

“You’ve done things that have been very concerning, okay? But at the same time, we want to make sure that we figure out what’s going on with you,” said the officer. “You understand what’s going on in the world today, right?”

Chris opened up. He had been researching a community called “braincels” — an offshoot of the banned “incel” subreddit, those angry young “nice” guys who feel entitled to companionship and sex. “I was in a pretty angry place, you know?” He talked about being “indoctrinated … with hate.” From a place of anger, and with a dash of trolling, he praised the killers. A part of him was “trolling,” he said. He wanted to find out whether Reddit would act on a comment like that.

Chris said he could understand how it happened. Cruz was into guns. He was bullied. And then one day... he just snapped.

“Do you see a little bit of yourself in Nicholas Cruz?” the officer prodded, gently.

“Not too much on the guns part — I barely know how to use one at all.” But “maybe on the bullying part, sort of.”

Officer Panter looked the troubled 21-year-old in the eye. “When did the bullying start?”

Confessing to dark thoughts

And so it went, the cop acting almost like a therapist, encouraging Chris to open up, to talk about his experiences as a quiet middle schooler. The officer earned Chris’s trust, urged him to say more. When Chris said people thought he was weird, and would play pranks on him, the officer talked about how hurtful that must have been. And yet he wasn’t afraid to push back on Chris when necessary. After Chris said he would “never, ever, act out in violence against anybody in a mass shooting or anything of the sort,” the officer responded: “How do I know that?”

“I need you to be honest with me,” the officer said. He didn’t believe that Chris had said that stuff just to test Reddit. “Why did you write that? Were you having thoughts at that particular time of doing something like that?”

“I can’t say if I was ever going to be committed to doing it,” Chris responded. “But I guess it passed through my head.”

“OK,” the cop went on. “Why do you think the thoughts were in your mind, that you were thinking about doing a mass shooting, or being a school shooter?”

And this is where the quiet, angry, troubled man revealed his deepest secret.

“I thought about the rush that must go through the shooter’s head as they’re, you know, rampaging through the school.” —Chris Velasquez

“I thought about the rush that must go through the shooter’s head as they’re, you know, rampaging through the school,” Chris said. “Knowing that they — no matter what happens then — they will be remembered.”

Over the next hour, Chris talked about his “hero” Stephen Paddock, the 64-year-old shooter who single-handedly committed the most deadly shooting in U.S. history, mowing down 61 concert-goers in Las Vegas from his perch 32 stories up at the Mandalay Bay, spraying 1,000 rounds into the crowd below.

I was “trying to picture myself doing what they did,” Chris said of the shooters. “It’s the adrenaline rush basically that I get when I picture, well, what those two — or anybody else who did a mass shooting — was going through. I guess for maybe that moment I idolized Stephen Paddock.”

From what the officer and other investigators could discern, Chris had never taken any steps towards planning out an actual attack. (If they had found any evidence of actual plans, Chris wouldn’t simply have been prevented from purchasing guns for a couple weeks; he’d have been charged with a crime.) But his “detailed homicidal ideation,” as a sergeant from the Orlando Police Department put it, was enough to ensure that — temporarily, just in case — Chris lost the ability to own weapons or ammunition.

Fighting red flag laws is ‘a losing battle’

Attorney Kendra Parris represented Chris in this case. After Florida’s red flag law was first passed, Ms. Parris made a name for herself defending people whose gun rights were stripped. Now?

“I’m not working on them much anymore,” she told Unprecedented. “It’s a losing battle.”

Now that police have this tool in their toolbox, they are using it. A lot. Florida courts have approved thousands of risk protection orders (RPOs). This amounts to several each day. “The sheriffs in Florida love it,” Ms. Parris said.

A couple of years ago, Ms. Parris took an Elle reporter with her to the Polk County courthouse to get a sense of what these orders were being used for. “There were four RPOs that day,” Ms. Parris told me. “One elderly gentleman who got mad at the insurance company rep over the phone for not paying for his wife’s insulin and said something about a ‘rocket launcher’; and three black middle schoolers.”

Chris’s temporary RPO was lifted almost as quickly as it was imposed. When it came before a judge six weeks later, the judge declined to turn it into a “permanent” (12-month) ban. “The Court finds that the City/Petitioner did not meet its burden to prove by clear and convincing evidence that Respondent poses a ‘significant danger’ requiring that a risk protection order be entered,” Judge Bob LeBlanc wrote.

It’s hard to come by exact statistics, but Chris’s case appears to be an exception. Most RPOs are granted. In 2020 the local NBC station found that 92% of the RPOs sought by Palm Beach County law enforcement were granted, and St. Lucie County had a 100% success rate.

Law enforcement might have been a bit overzealous toward Mr. Velasquez. He didn’t own any guns. There was no evidence he was planning to buy guns. He didn’t have a criminal record. “My client was tried, convicted, and crucified by the media before we could set the record straight," Ms. Parris told Reason Magazine after the ban was lifted. In the wake of the Parkland massacre, she says, “Everybody is extraordinarily hypersensitive and emotional, and there was no room or time for nuance and context, evaluating the facts.”

But other Floridians’ red flags have arguably been much worse. In just the last two months, one Florida judge has restricted the gun rights of:

A dad accused of threatening to "shoot everyone" at his son's school, a woman who police say attempted suicide and then accidentally shot her boyfriend during a struggle for her revolver, a husband who allegedly fired multiple rounds in the street to "blow off steam" after losing a family member, a bullied 13-year-old witnesses overheard saying, "If all of 8th grade is missing tomorrow, you will know why," and a mother arrested for brandishing a handgun at another mom after a school bus incident between their daughters.

It’s difficult to say whether red flag laws make any measurable difference in the overall rate of gun violence. How can anyone prove that the government changed the future? That if not for these confiscations, a crime would have occurred? They can’t — though some have tried. One study found that after California enacted its red flag law in 2016, none of the people who received RPOs went through with a mass shooting after threatening one. (Again, however, it’s impossible to say whether the RPOs stopped the shootings, or if the threats were just hot air to begin with.)

So what’s the problem?

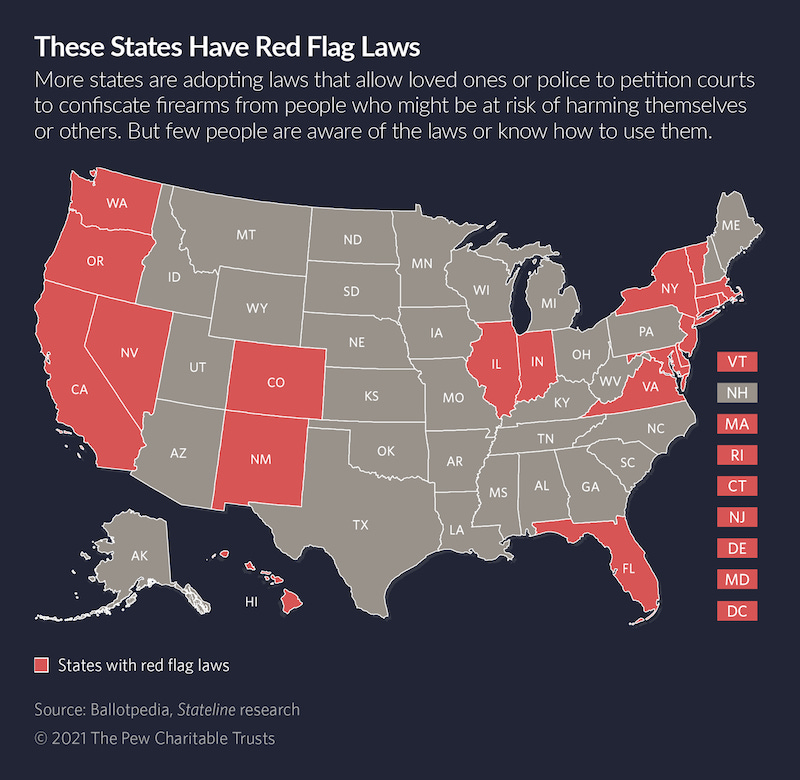

Regardless of the lack of hard evidence of their effectiveness, red flag laws are popular. Nineteen states already have them on the books, and last week the U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill that would give federal courts the ability to issue RPOs (they’re currently strictly a creature of state law).

So if there is so much agreement between Democrats and Republicans on their possible benefits, what’s the hold up? Why are so many people warning that the current tentative Senate agreement is far from a sure thing? That the House’s red flag bill will go nowhere? That these laws might themselves be unconstitutional?

Because, say many conservatives and civil libertarians, red flag laws run roughshod over so many constitutional protections.3 The National Rifle Association, as you might imagine, has warned they’re just a way for judges to “nullify” the protections of the Second Amendment. They treat “due process” as an inconvenience: Even though Mr. Velasquez had his RPO revoked as soon as a judge was able to give him a hearing, that’s still six weeks when he couldn’t have purchased a gun even if he had wanted to.

And it’s not just the NRA that has a problem with these laws. In 2018, the American Civil Liberties Union of Rhode Island said it was “deeply concerned” about a proposed red flag law there, its potential impact on civil liberties, and “the precedent it sets for the use of coercive measures against individuals not because they are alleged to have committed any crime, but because somebody believes they might, someday, commit one.”

And that’s before even taking into account the First Amendment’s protection against laws abridging the freedom of speech. “True threats” aren’t protected, but idle threats? Hyperbole? Haha, just kidding? That’s the grey area on which many constitutional lawyers build their careers.

‘I want to shoot him in the face’

Few courts have looked at the constitutionality of red flag laws. That’s not surprising, since such laws are fairly new. While court decisions are hard to come by, Ms. Parris did admit that “there is one out of the First [District Court of Appeals] in Florida but it’s genuinely one of the worst opinions ever drafted so we all pretend it doesn’t exist.”

(Note to attorneys, PR professionals, and anyone else who is trying to downplay unhelpful evidence: This is how you intrigue a reporter.)

The 2019 case was the first to field a challenge to Florida’s red flag law after the Parkland shooting. And, like most scenarios that trigger an RPO, the facts are juicy. This newsletter is running the risk of becoming a novella, but if you’ve made it this far, you deserve a fun break. Story time:

Two police officers were dating each other. But the male police officer suspected his girlfriend of cheating on him. While off-duty, he came to the station and confronted his girlfriend. When another cop tried to intervene, the officer threatened him. He punched a solid wood door and a filing cabinet, and inexplicably fell to the floor — out of grief? Despair? Who knows. The officer later texted his supervisor — the county sheriff — and asked for his help, warning that “something bad was going to happen.”

When the officer and his boss met up, the officer said that he wanted to kill his girlfriend’s lover using his police-issued gun. “I want to shoot him in the face, eat his food, and wait for [law enforcement] to pick me up,” he said, according to court records. He later said something similar to two other fellow officers, noting that he would use the handgun in his car and aim for “between the eyes.” Some of his coworkers thought he was having a mental breakdown.

Pretend you’re a judge

You’ve attended one class at the Unprecedented School of Law. You’re basically qualified to pretend you’re a judge. Is this the kind of guy you’d OK a red flag law for?

The law directs a court to issue an RPO if it finds “by clear and convincing evidence” that if the person has access to a gun, he “poses a significant danger of causing personal injury to himself or herself or others.” Do the officer’s words and actions count as “clear and convincing” evidence that he would hurt someone?4

(The phrase “clear and convincing” is a term of art, but it basically falls somewhere between the burden of proof in a civil case and the burden of proof in a criminal case. In other words, it has to be more than simply “more likely than not” that someone posts a significant danger to themself or others — but it doesn’t need to be “beyond a reasonable doubt.” Think of it as “pretty damn likely.”)

The first judge to look at the facts said the officer did pose a significant danger. The appeals court found that conclusion reasonable. “When evaluating hostile words ... we recognize trial judges are often faced with the difficult task of differentiating between facetious or hyperbolic declarations meant to ‘blow off steam,’ and those manifesting a genuine threat,” the court wrote. Although it’s possible those hostile words were just hollow threats, “we find the record supports a more ominous conclusion. The threats were specific and graphic and made by someone with the wherewithal to carry them out.”

The officer’s attorney also challenged the constitutionality of Florida’s red flag law, arguing the language of the statute was vague — what exactly does it mean to pose “significant danger”? — and that it violated suspects’ due process by potentially punishing completely innocent activity.

The court quickly rejected the challenge. The language of the statute is perfectly clear, it said. There are plenty of safeguards in the law to make sure it’s not applied improperly — such as the requirement for a quick court hearing. And “clear and convincing” evidence is a relatively high bar; a judge can’t just take away someone’s guns because she feels like it.5

Red flag laws have survived a few court challenges at the local level

Second Amendment challenges to red flag laws haven’t gotten very far. The few courts to field those arguments have quickly shot them down. “The United States Supreme Court has recently and repeatedly recognized the legitimate governmental purpose of prohibiting the mentally ill from possessing firearms,” an Indiana court wrote in 2013. A Connecticut court ruled similarly a couple years later.6

The federal courts haven’t weighed in, perhaps because as yet there are no federal statutes to challenge; these laws are enacted at the state level. (With the House’s passage last week of its federal RPO law, however, we may be getting closer to opening the doors for a federal challenge.)

The Supreme Court hasn’t yet had the opportunity to consider whether red flag laws are kosher, but they could soon get the chance. Last year, in a concurrence to a unanimous decision throwing out a warrantless confiscation of a gun from a mentally unstable person’s home, Justice Samuel Alito idly contemplated what might happen if and when red flag laws were to appear on the docket:

This case also implicates another body of law that petitioner glossed over: the so-called “red flag” laws that some States are now enacting. ... They typically specify the standard that must be met and the procedures that must be followed before firearms may be seized. Provisions of red flag laws may be challenged under the Fourth Amendment, and those cases may come before us. Our decision today does not address those issues.

It’s not a matter of if the Supreme Court will weigh in on their constitutionality. It’s a matter of when.

In Conclusion

State legislatures are enamored by red flag laws. Now the federal government is excited about their possibility as well. But there are several unanswered questions, and given the potential constitutional issues, they may not be the panacea their supporters believe they are.

We’ll have to wait and see whether the federal courts believe the state’s interest in protecting the public from the possibility of violence outweighs a person’s fundamental rights to free speech, the right to bear arms, the right to be free from unreasonable search and seizure, and the right to due process.

In the meantime, Americans and their lawmakers agree: Red flag laws are currently the best tool we’ve got in our toolbox to try to stop the next mass shooting before it begins.

And that’s the Schwartz Report! We’ll be back in a day or two with the legal roundup. If you’ve enjoyed this newsletter, please leave a comment, forward it to a friend, click that little heart button on the website, and share it far and wide. And if you really want to support my work, please consider becoming a paying subscriber. You’ll be supporting all the work we do here at Unprecedented, and you’ll also get access to occasional subscriber-only bonus segments.

Thank you for your support!

Sincerely,

Matthew S. Schwartz

Editor of Unprecedented

Apologies for mixing church and state.

It is irrelevant, but interesting to note here, that saying violent things on Reddit is not the only way to guarantee yourself a conversation with a UCF officer. There is another way, which is potentially much more fun and energizing. (Still, I wouldn’t recommend it.)

The law goes on to provide 15 examples of the kind of evidence a judge can consider, including a recent threat against himself or others (gun-related or otherwise); an act of violence within the past 12 months; evidence of mental illness; a prior conviction for domestic violence; evidence of a recent firearm purchase; evidence of use of drugs or alcohol; testimony from family members; and basically anything else the judge wants to look at. The court clearly has broad discretion to issue an RPO. That’s the point: The legislature wanted a judge to be able to err on the side of caution and take away guns from anyone who might be a threat.

Ms. Parris elaborated on why she considered the decision so awful. “The reason I said that 1st DCA case is terrible is because the court stated it implicated strict scrutiny but never even bothered to explore the 'narrowly tailored' prong at all,” she told Unprecedented.

This is one of those statements that makes perfect sense to lawyers, but likely seems somewhat impenetrable to regular people. Suffice it to say, this is a legitimate critique of the ruling. When reviewing laws that impair the exercise of a fundamental right (in this case, the right to bear arms), a court is supposed to look not just at whether the state’s interest is “compelling,” but also whether the law was “narrowly tailored” to achieve that interest.

It’s pretty easy to make an overbreadth argument here, and the fact that the court never even acknowledged this prong of the test does arguably make it “terrible” (not a term of art).

I wouldn’t put too much stock into the Connecticut opinion though; the challenger represented himself without an attorney. And you know what they say about people who represent themselves.

Since I don't consider the right to bear arms a fundamental right, I don't have a problem with anybody who's even been rumored to have joked about shooting someone having their guns taken away.